This is the first in a series of posts from Andy Cargile, Senior Director, User Experience at SMART. Andy leads a team of user experience designers and researchers who spend hundreds of hours in classrooms every year, delving into teaching, learning, and how technology can enhance them. In this series, Andy shares some of the key insights his team has uncovered, and what they mean for education.

“Torturous.” “Savage.” “Death.”

These are real comments from kids about…fractions.

Fractions are a common and unifying subject which most kids, most parents and many teachers passionately dislike. They also present a great opportunity to look at why some subjects in school get reputations like this and how, through better understanding kids, teachers, and parents, we can help change that.

Most kids can learn really well on their own. They’re just a little particular about what they choose to learn. This was one of many insights we gleaned by going out in the field to watch how kids learn outside of school. Our goal was to bring back such insights and apply them to what we do at SMART to develop better tools for teachers, parents, and, above all, learners.

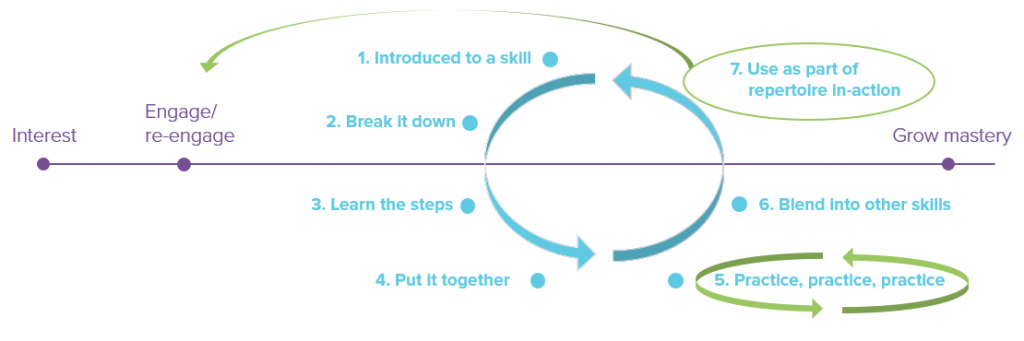

We observed a lot of kids and talked with them about how they learn things that they care about – everything from sports and hobbies, to music, to doing scary flips on Razor scooters. We boiled it down to a basic learning process that resembles the one kids find themselves in at school, but with a few key differences.

One of the biggest differences is that outside of school, kids can usually learn at their own pace, whether with instruction or on their own. They have some control of their learning. They can try things until they “get” them if they are motivated.

Learning at their own pace is important for kids because a key component of this process is steps 2-4: breaking it down, learning the steps, and putting it all together.

This is often where kids get lost in school with a particular subject – like fractions. If they don’t really “get” the subject in steps 2-4, then the “practice, practice, practice” stage – which usually involves a lot of homework and testing – doesn’t help them. Then they get frustrated.

One young girl told us that they “raced” through fractions and she never really understood them. But, “…I know we’ll only do those for a few weeks and then we’ll be on to something else, so I’ll just ignore these.” Fractions are a key component of advanced math, and something about the process of learning them taught her only to give up.

Another key difference is step 7: use the concept as part of the repertoire in-action. It’s essentially real-world application. We’ve all heard this a lot from kids: “why do I have to learn X; I’m never going to use it.” When kids do see value, it motivates and re-engages them in the learning process and the process can become a “virtuous cycle.”

It happens to kids all the time when they discover something they love and are passionate about. Sadly, school subjects (and especially math) fall prey to not passing muster on real-world value.

Teachers do the very best they can, but teaching complex concepts to 30 young kids at a time, at their own pace, with an ever-increasing workload, is daunting.

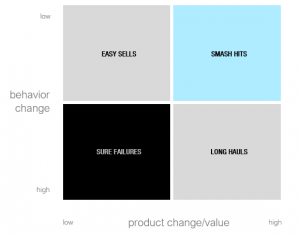

My background is in technology, management and UX, and this problem reminds me of Gourville’s model for product success (2006), which articulates a very similar challenge. Except instead of how to get students interested in fractions, it proposes how to get people interested in a product.

Basically, products that require users to change very little of their usual behavior and add a lot of value are usually successful. Ones that require users to change their behavior for little gain are sure to fail. From the perspective of many kids, especially with subjects like fractions, guess where school falls.

We found that kids are generally pretty fearless about trying and learning new things on their own. Some attempts work out, some don’t, and kids are generally okay with that. We also found that they are more enthusiastic and try harder when:

- They can work at their own pace until they “get it”

- They’re given context for why they should care

- They can access the material in a way they perceive as fun

Game-based learning is one approach we are using to develop a new set of products that addresses all these conditions, but that’s another subject for another time.

In our research, we’ve had the privilege of witnessing extraordinary learning moments. We’ve seen teachers reach students on a level that has brought out the greatness within. Our singular mission is to give all teachers the tools to do this more: to augment kids’ learning and help them achieve greatness. Or, at the very least, get past what one ten-year-old called the “boss monster of math”: fractions.